Our Water: The Dilemma and Convenience of PFAS

Check out original article from TriCountry Regional Planning Committee

Figure 1. Photo of PFAS foam from MPART site.

Each year as the weather warms up, individuals and families all across the state head outside to enjoy the fleeting warmth by flocking to one of our many lakes, rivers, or smaller bodies of water to boat, swim, fish, and enjoy our state’s spectacular water resources. During these long summer days, you might have noticed white foam along the shoreline or gathering in clumps out on the surface of the water. Though foam can be naturally occurring, this substance could also be the result of chemicals in the water, commonly referred to as PFAS, a catch-all abbreviation for the thousands of manmade chemicals known as per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances. Because PFAS chemicals prevent other materials from bonding to them, their heat-, stain-, and water-resistant chemical properties have proven useful and convenient for products we use in our everyday lives. Even your favorite non-stick cooking pan or the pair of boots you grab on a rainy day contain PFAS!

Manufactured since the 1940s, these chemicals have been used in products like food packaging, water- and stain-resistant fabrics, cleaning supplies, and fire extinguishers, just to name a few. Because these chemicals are very stable and do not break down easily, they are commonly used in mass-produced items. This also means they can accumulate over time in any natural environment, including our bodies. In more recent years, additional research has been called for and conducted to learn more about PFAS and the long-term impacts these chemicals may have on people and our environment.

Figure 2. Chemical structure of PFAS.

Of the many thousands of PFAS chemicals known to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), two types, PFOA and PFOS, are no longer manufactured in the United States, largely thanks to initiatives like the PFOA Stewardship Program, which was dedicated to discontinuing PFOA production in favor of more affordable and less damaging alternatives. It should be noted that while they are no longer produced in the U.S., many of these chemicals, including PFOA and PFOS, are still produced internationally and can be imported for use in U.S. manufactured goods sold on the market. These contaminates can make their way into our environment and waterways from sources like manufacturing and processing facilities, airports, landfills, waste treatment plants, military installations, and firefighting training facilities. To mitigate these concerns about the possible impacts of PFAS contamination, many agencies and organizations have taken action to limit our exposure to these chemicals. As of January 2016, the FDA no longer allows PFOA and PFOS to be added in food packaging, and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is working toward establishing rules to close loopholes allowing PFAS chemicals to be imported by foreign suppliers.

While these PFOA and PFOS regulations are a noteworthy step in curbing the chemical substances contaminating our environment, the necessity to better understand the impacts of PFAS in our lives persists. One of the biggest issues with PFAS? We’re still figuring out how it can impact our health. While consumer products and food pose the largest risk of exposure to PFAS, drinking water has been found to be a source of PFAS in a small percentage of communities with a chemically polluted water supply. The quality of what we put into our bodies has a direct impact on our ability to lead a healthy life, and PFAS is no different. To better understand the potential health impacts of PFAS, scientists have relied on data collected from animals, which have thus far indicated evidence of issues in reproductive and developmental health, liver and kidney damage, and negative effects on their immunological systems. Some human health studies have shown similar results, indicating that large-scale exposure to PFAS could be a potential cause of infertility, increased likelihood of thyroid disease, higher cholesterol levels, changes in immune responses, and a number of cancers.

It’s estimated that nearly 95 percent of all U.S. residents have been exposed to various concentrations of PFAS and could have measurable concentrations of it in their blood. However, it’s crucial to note that even consistent exposure to PFAS does not mean you will necessarily experience any health issues. As the Michigan PFAS Action Response Team (MPART) also points out, if you have health problems, it’s hard to be certain those problems were caused by PFAS. To prevent exposure to large concentrations of PFAS and to protect our most sensitive populations, the EPA has issued a combined 70 parts-per-trillion (ppt) health advisory level for PFOA and PFAS. This means that if you had roughly 6,000 Olympic-sized swimming pools full of water, only 70 teaspoons of that water could be PFAS chemicals. For reference, this is a very small number in comparison to permitted concentrations of regulated substances such as arsenic, which has a limit of 10 parts per billion; copper, at 1.3 parts per million; or fluoride, at 4 parts per million. Although this health advisory level is not an enforceable or regulatory action, it is a good opportunity to provide PFAS guidance to communities while the EPA conducts their four-step action plan to better regulate the use of and exposure to PFAS chemicals.

While we await final regulatory action on the federal level, many states have passed their own regulations and action plans to help prevent unnecessary PFAS exposure. Here in Michigan, former Governor Rick Snyder and the Department of Environmental Quality [now the Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy (EGLE)] worked to establish MPART in 2017. They began the first phase of their PFAS response by conducting a statewide surveillance test of public drinking water sources for 7.7 million of Michigan’s 10 million residents in April 2018 (as the remaining 3.3 million residents receive their drinking water from private well systems). This included collecting samples from community water supplies, personal school wells, daycares, Michigan Head Start program locations, and tribal water systems. Based on the results of those samples, only three suppliers were found to have PFAS levels above the recommended EPA health advisory level. Since then, each of the communities that were found above the desired PFAS levels have been working closely with EGLE to reduce their levels.

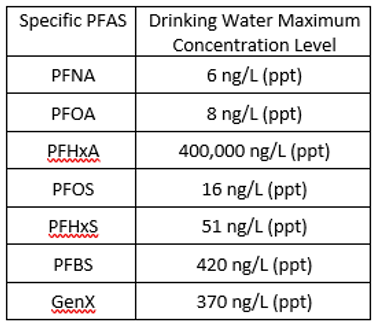

In 2019, MPART moved on to phase two: regular testing of water suppliers on a monthly or quarterly basis depending on their initial measurement below the advised 70 ppt. While this testing is still ongoing, new PFAS standards for drinking water have been recently approved by the Michigan Environmental Rules Review Committee and went into effect on August 3, 2020. These rules will now require Michigan’s approximately 2,700 water suppliers to regularly test for the presence of seven common PFAS chemicals (provided in Table 1) using the EPA-developed laboratory method for identifying PFAS contamination in drinking water. Though there is not yet a “one-size-fits-all” method for the removal of PFAS, Michigan has removed and properly disposed of more than 30,000 gallons of PFAS fire-fighting foam in the last year, estimated as the nation’s largest PFAS removal effort to date.

Figure 3. Drums of collected PFAS firefighting foam.

The good news about PFAS? Any concerns you may have about your or your family’s exposure via drinking water can easily be addressed with a few steps toward precaution and prevention. First, if you are unsure whether your water has PFAS in it, ask your local health department! You can work with representatives there to determine the next steps to have your water tested for PFAS. If you do receive results indicating there is PFAS in your drinking water and it is above the EPA lifetime health advisory level or the PFAS regulations set by Michigan, get in touch with your local water provider. If you have a private well, investigate possible alternative water sources or consider installing a filtration system on your property.

Though PFAS is likely here to stay and you don’t necessarily need to throw out your favorite non-stick pan, it’s fairly easy to avoid coming into contact with unhealthy concentrations and to support responsible oversight and regulations. By keeping up with regular water testing, educating yourself about how much PFAS may be in products or foods, and keeping away from and reporting that foam on the shoreline, you’re doing your part to help protect everyone’s environment and your wellbeing.

For more information about PFAS, visit the Michigan PFAS Action Response Team website.

Contact Lauren Schnoebelen, our Environmental Sustainability Planner and coordinator of the Groundwater Management Board, to learn more about regional groundwater and drinking water issues.