Failing septic systems a cause for concern

Michigan is the only state in the nation without uniform standards governing how on-site sewage treatment systems are designed, built, installed and maintained. Filling this gap, health officials say, would address the single biggest problem with septic systems: the lack of maintenance. Skip ahead to some simple tips homeowners can follow to protect their septic systems.

The State of Michigan estimates that roughly half of its rivers and streams exceed the safety standard for concentrations of E. coli bacteria. Escherichia coli (E. coli) is a type of bacteria that serves as a key water quality indicator. Because E. coli grows naturally in the gastrointestinal tract of warm-blooded animals and humans, its presence in a water sample tells us that fecal pollution has reached that water source by some means.

What does this have to do with septic systems? Septic systems are a form of onsite sewage treatment common in rural Michigan communities, homes surrounding lakes, and throughout some suburban communities as well.

Household wastewater is sent to a large tank, where anaerobic bacteria break some of it down before allowing the water to flow out of the system into a drainfield for further filtration by the soil. Learn more about how septic systems work and their basic components.

More than 1.3 million homes and businesses in Michigan depend on septic systems to treat wastewater. The Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes & Energy (EGLE) estimates there are 330,000 failing systems currently operating in Michigan. That represents around 25% of the 1.3-million systems installed statewide. EGLE further estimates that Michigan’s numerous failing septic systems release upwards of 31 million gallons of raw sewage every day into our groundwater. Sometimes a failing septic system is obvious to the homeowner and is repaired or replaced quickly. But system failures can also easily go unnoticed and unrepaired for years.

If not maintained, failing septic systems can contaminate groundwater and harm the environment by releasing bacteria, viruses, and household toxics to local waterways. Proper septic system maintenance protects public health, the environment, and saves the homeowner money through avoided costly repairs. If we want to keep E. coli and other pathogens out of our waterways, we need to address the problem of septic systems that may be failing to adequately treat our wastewater.

County health departments regulate where septic systems can be installed, but the regulations end there for much of the state. Only 11 of Michigan’s 83 counties have gone beyond existing state regulations and enacted programs designed to detect failed septic systems and force repairs.

This is an issue because 45% of Michigan residents rely on groundwater aquifers for their drinking water (EGLE, 2018). In addition, the sewage makes it to our beaches and other bodies of water where it makes it dangerous for people to swim due to the elevated E. Coli levels.

Our water is a shared resource. What one person does on their property, impacts the water quality for all the surrounding neighbors. We have a shared responsibility to maintain our septic systems for the health of Michigan’s residents.

So, what can be done? Septic tanks should be pumped out every three to five years to prevent back-ups. The average lifespan of a septic system is about 20 years, according to government and industry officials. Replacing a failed septic system costs between $5,000 and $20,000. It is often more cost effective to get your septic system pumped and maintain it than to pay to have one completely replaced.

Watch the video below to learn tips about septic system maintenance.

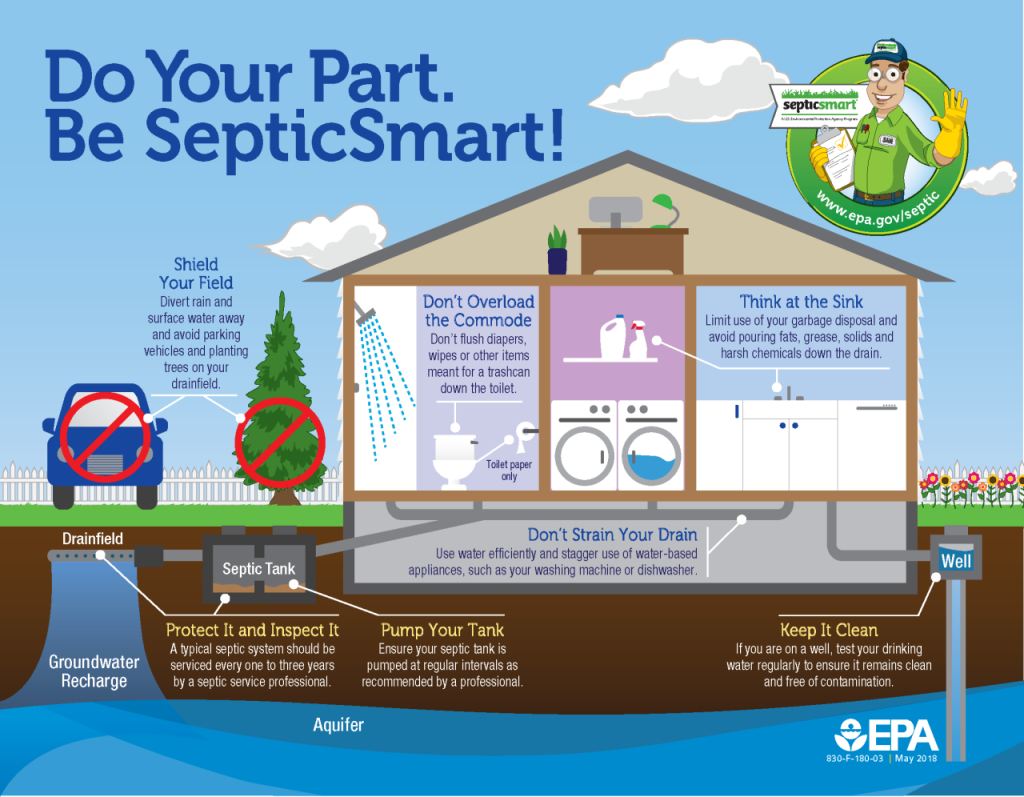

Simple Tips for Homeowners:

Protect It and Inspect It: Homeowners should generally have their system inspected every three years by a qualified professional or according to their state or local health department’s recommendations. Tanks should be pumped when necessary, typically every three to five years.

Think at the Sink: Avoid pouring fats, grease, and solids down the drain. These substances can clog a system’s pipes and drainfield.

Don’t Overload the Commode: Only put things in the drain or toilet that belong there. For example, coffee grounds, dental floss, disposable diapers and wipes, feminine hygiene products, cigarette butts, and cat litter can all clog and potentially damage septic systems.

Don’t Strain Your Drain: Be water-efficient and spread out water use. Fix plumbing leaks and install faucet aerators and water-efficient products. Spread out laundry and dishwasher loads throughout the day – too much water at once can overload a system that hasn’t been pumped recently.

Shield Your Field: Remind guests not to park or drive on a system’s drainfield, where the vehicle’s weight could damage buried pipes or disrupt underground flow.

Pump your Tank: Routinely pumping your tank can prevent your septic system from premature failure, which can lead to groundwater contamination.

Test Your Drinking Water Well: If septic systems aren’t properly maintained, leaks can contaminate well water. Testing your drinking water well is the best way to ensure your well water is free from contaminates.

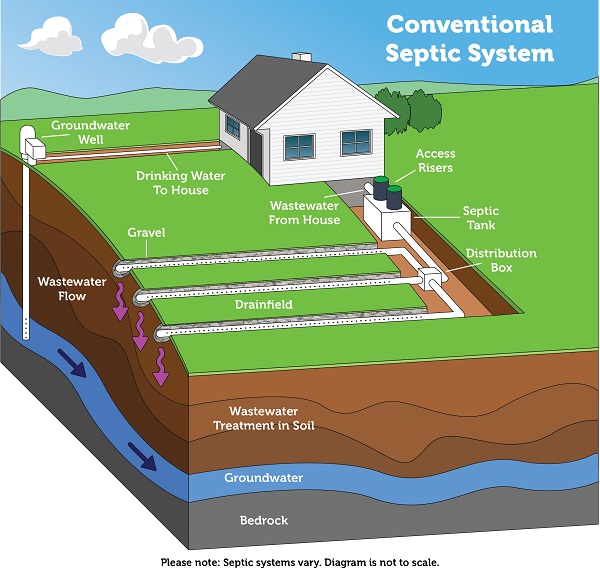

How a Septic System Works

Wastewater from sinks, showers, and toilets flows into a septic tank through the home’s main line.

Inside the tank:

- Sludge (solids) settles at the bottom.

- Scum (oils and grease) floats on top.

- Effluent (liquid) stays in the middle.

Anaerobic bacteria in the tank break down some of the solids. Effluent flows out through baffles and filters, moving to the drainfield. In the drainfield, effluent filters through gravel, sand, and soil. Aerobic bacteria and other microorganisms further break down waste, purifying water before it reenters the groundwater.

Primary Components of a Septic System

- Main line – Underground pipe carrying wastewater from the house to the septic tank.

- Septic tank – Watertight container (usually 1,000–1,500 gallons for homes) that holds wastewater and separates solids, liquids, and scum.

- Access risers – Vertical capped pipes that allow professionals to pump or inspect the tank.

- Baffles – Direct wastewater flow in and out of the tank, preventing solids from leaving with the effluent.

- Effluent filter – Extra filter (in some systems) to block scum or sludge from exiting the tank.

- Drainfield (leach field/absorption field) – Underground area where effluent is released and filtered through soil.

- Sludge – Heavy solid waste that sinks to the bottom of the tank.

- Scum – Oils, grease, and lighter materials that float to the top.

- Effluent – The liquid portion of wastewater that leaves the tank for treatment in the drainfield.

- Anaerobic bacteria – Break down sludge inside the tank (no oxygen needed).

- Aerobic bacteria – Break down organic matter in the drainfield (require oxygen).